Second workshop in the Series: Plot & Development with Helen Hagemann

Friday, 21st August 2015 1.00-3.00pm, Room 3, Fremantle Arts Centre.

Cost: $20 OOTA $25 NON-OOTA

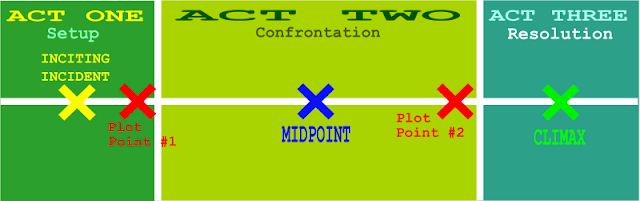

This workshop "How to write an outline" includes writing a novel or short story outline of one of your favourite authors, and by utilising a template of Helen Hagemann's "3 Act outline" of her novel The Ozone Cafe. There will be an exercise on writing your own "outline", as well as class discussion on choice of genre, point of view, timeline, and choice of tense.

Outlining by Lawrence Block

An outline is a tool which a writer

uses to simplify the task of writing a novel and to improve the ultimate

quality of that novel by giving him/herself more of a grasp on its overall

structure.

And that’s about as specifically as one can define an outline, beyond

adding that it’s almost invariably shorter than the book will turn out to be.

What length it will run, what form it will take, how detailed it will be, and

what sort of novel components it will or will not include, is and ought to be a

wholly individual matter. Because the outline is prepared solely for the

benefit of the writer himself, it quite properly varies from one author to

another and from one novel to another. Some writers never use an outline.

Others would be uncomfortable writing anything more ambitious than a shopping

list without outlining it first. Some outlines, deemed very useful by their

authors, run a scant page. Others, considered equally indispensable by their authors, run a hundred pages or

more and include a detailed description of every scene that is going to take

place in every chapter of the book. Neither of these extremes, nor any of the

infinite gradations between the two poles, represents the right way to prepare

an outline. There is no right way to do this – or, more correctly, there is no

wrong way. Whatever works best for the particular writer on the particular

book is demonstrably the right way.

The writer who does not use an outline says that to do so would gut the

book of its spontaneity and would make the writing process itself a matter of

filling in the blanks of a printed form. At the root of this school of thought

is the argument first propounded, I believe, by science-fiction author Theodore

Sturgeon. If the writer doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, he argued,

the reader can’t possibly know what’s going to happen next.

The writer who does not use an outline says that to do so would gut the

book of its spontaneity and would make the writing process itself a matter of

filling in the blanks of a printed form. At the root of this school of thought

is the argument first propounded, I believe, by science-fiction author Theodore

Sturgeon. If the writer doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, he argued,

the reader can’t possibly know what’s going to happen next.

There’s logic in that argument, certainly, but I’m not sure it holds up.

Just because a writer worked things out as he went along is no guarantee that

the book he’s produced won’t be obvious and predictable. Conversely, the use of

an extremely detailed outline does not preclude the possibility that the book

will read as though it had been written effortlessly and spontaneously by a

wholly freewheeling author.