A Scene from Chapter 14

Winifred skirted her bike in the front

courtyard, and pitched her voice towards Vincenzo. ‘I have to get home for a

minute. I’ll be back soon. I’ve got a present for you. Wait and see. You’ll

love them.’

Nothing held him back now, Vincenzo whistled

as he dragged the teeth of the rake through the leaf litter. ‘That girl,

Pomadina,’ he said, the dog looking up expectantly, ‘is full of surprises. Here

I am, raking, waiting to show them my mural, and she is building up suspense

like a great Italian film.’

In a flash he heard a knock at the front

door. Casey was looking into the café’s darkness with cupped hands, while

Nicolas was parked under the jacaranda.

‘I’m round here, kids,’ called Vincenzo. ‘I

wait for the big moment, hey? Mainly for the time yous all turn up together.’

‘Where’s Winifred,’ asked Casey.

‘She be a minute. Gone home first. Here,

come around to the side near my canvas. I have some Coca-Cola for you.’

Vincenzo bent down, picking up the last of his sweepings, placing the contents

in a metal bin. They sat under one of the umbrellas while Nicolas spun his

wheelchair on the spot, stirring Pomadina into a game of growling.

‘Why have you got it covered up,’ said

Casey. ‘Can’t we have a look now?’

‘Uh, uh,’ said Vincenzo, waving his finger.

‘We wait. We be all together. This is special moment in Vincenzo’s life. I

never did anything like this before, and well, we see.’

Vincenzo lifted the caps off the Coca-Cola,

handing the bottles to the children. They sat quietly for several minutes,

until Casey chattered on about her sports day at school. She finished her drink

and handed the bottle back to Vincenzo. ‘Mr. Polamo, why Is the café all dark

inside. Is there a black-out?’

‘Na, but I got a big surprise for you kids,

and….’

At that moment, Winifred climbed the steps

and stood puffing with her stomach bent over. ‘Made it in five,’ she said,

taking in long breaths, and handing Vincenzo a package wrapped in newspaper.

‘You needn’t unwrap it, it’s just fish. Dad

caught a bucket-load last night off the heads. I think he’s given you a red

snapper, too.’

Vincenzo’s heart stirred. He noticed this every

time someone showed him some kindness. Winifred’s family was the type of people

he had come to call his own. He had been to their home, played scrabble and

dominoes with Winifred’s brothers, had supper at the table, and walked Pomadina

there and back, just to have a friendly chat and cup of tea with Marcia,

Winifred’s mother. It was only a couple of times, but they would listen

intently to Vincenzo’s stories about his family back home. He hadn’t seen

Rennie since the building project finished, so they were his new friends.

‘I put them in the fridge later,’ he said,

waving to the children to come closer to the wall. ‘Okay, the big momento.’

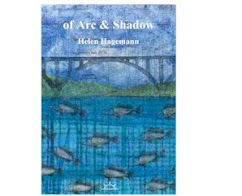

Vincenzo untangled the rope from two hooks at the top of the

wall, and lowered the tarpaulin. There, as if the sea had planted its

impression on the wall, was a large seascape, a buoyant ship, its hull disappearing

into the waves. At the helm was King Neptune, his tunic billowing in the wind,

right arm pointing forward, a raised fork holding back the massive curls on his

head. Further along the wall, and

sloping down towards the front of the café, were the rippled indentations of

the ocean and its shoreline. A shark fin pointed between the extrusions of

cement, and the sand was dotted with tiny mollusk shells and periwinkles. Two

starfish curled at the water’s edge. Larger still at the end of the mural, and

lazing on a web of rock, were two mermaids; one child size and the other almost

like a teenager. Their tail fins draped in a reclining pose. One mermaid looked out to sea with her hair trailing

behind, while the other stared gainfully at a tiny crab crawling along her arm.

Vincenzo beckoned the children to come closer, to put their fingers into small

crevices on the wall. Deep within the surface of the rocks he’d drawn the words

‘Winifred’ and ‘Casey’. And on King Neptune, across the front arc of his crown,

he’d written the word ‘Nicolas’.

Vincenzo crossed his arms and moved back

away from a slither of sunlight into the shade, studying his work at some distance.

Any minute now, he thought, he would go crazy if the children didn’t say

something, until finally he said, ‘Well, what you think, kids?’

‘Yeah, we like it,’ said Winifred.

‘Is that all? You don’t like something?’

queried Vincenzo, puzzled at the quietness of Casey and Nicolas.

‘Nah,’ said Winifred.

‘Well, what you think? Casey, you like?

Nicolas, you big King now.’

‘You have to give us time, you know, Vin,’ said

Winifred. ‘We weren’t expecting…well, I mean we didn’t know what it would look

like. We’ve only seen pictures of Jason and the Argonauts in our school library

books. We’ve never seen anything so…so beautiful ever, ever, and you’ve got us

in the picture. We didn’t know you’d put our faces and names there forever.’

Casey and Nicolas moved back further into

the courtyard, Casey pulling Nicolas backwards until both folded their arms in

front, studying the mural as if they were art critics ready to find fault.

‘Bravo!’ yelled Nicolas, almost standing in his

wheelchair.

The sudden sound, coming from such a quiet

boy, took Vincenzo by surprise. ‘Oh, you had me worried there, boy. I thought

you didn’t like it, hey?’

‘Bravo!’ yelled Casey, in likeness to Nicolas’s

outburst, thrusting both arms in the air.

‘Bravo!’ Winifred rejoined, grabbing

Vincenzo’s hand and shaking it vigorously. And their loud clapping, continued

on and on until they all grew tired of Pomadina’s incessant barking.

Vincenzo placed a finger in the air, and said,

‘Wait here, there’s more.’

He returned with a plastic bucket and lid.

‘Open it,’ he said, to Winifred.

‘Paddle Pops, yippee!’

‘Yep, one each. We celebrate - Vin Polamo’s

finally gone and done something right, ‘cause of you three.’

The children fell silent eating their

ice-creams. The sea lay before them, unhurried, yet busy nippers seemed to claw

their way sideways along the wall. The children made a sudden discovery of the

galaxy of stars; the limpets glowing a silver luminescence. The starfish seemed

to be holding a tentacle each, as if circling in a Mexican dance. The rainbow fish

rubbed noses and the moon had a face, with depressions like Swiss cheese. The

fading sunlight caught each child’s face in a perfect family likeness. They

gathered closer in to the mural, pointing, laughing, touching its surface and

looking back at Vincenzo’s beaming face.

Each little finger traced over a shell, a necklace, a mermaid, or a

ship’s mate holding a conch shell to his ear.

Vincenzo, preempting Winifred’s next question

said, ‘And young Bella, no shells left. They all used, hey?’

‘We think it’s wonderful,’ said Winifred.

‘Can we tell all the kids at school?’

‘We tell everybody,’ said Vincenzo. ‘Even

the Satara Herald.’

‘Wow!’ they all repeat.

‘We better put the fish in the fridge,

otherwise it’ll be stinkeroony,’ said Winifred.

All three waited at the front, Nicolas

holding Pomadina on his lap, as Vincenzo unlocked the doors.

‘Boy, it’s dark in here,’ said Casey.

A flutter of electric light beamed down on

their faces, and as Vincenzo bent down to flick the jukebox switch, he had to

cover his ears with the high-pitched screaming. The children’s voices, piercing

the air like the wails of hyenas after a kill. Their eyes and faces glowed in

the purple light of the jukebox. Vincenzo removed his hands, telling them to listen

to the first record he chose. Marty Robbins’ El Paso, then he had queued in Johnny Ray’s Just a walkin’ in the rain.

Winifred and Casey began to march back and

forth in the aisle, pretending to twirl umbrellas, while Nicolas discovered the

Table Soccer at chest height.

‘I make better plans now,’ said Vincenzo.

Soon I use deep fryer for fish and chips. I sell Paddle Pops, Twin Poles and

Wafers. I do lunch of salad sandwiches on white bread, yes Casey. Maybe some

fairybread, but I dunno. And I will order in the biggest pool table you have

ever seen.’

Winifred and Casey gathered around the

jukebox, pointing to all the songs they had heard on the wireless. ‘Where?’ said

Casey. ‘There,’ Winifred pointed. ‘Oh, he’s got Itzy Bitzy and Crash Craddock

too.’

Vincenzo pulled down the front blinds and

turned his sign to CLOSED. He was so overwhelmed by the day, telling the

children that he needed a nap. He told them they could keep playing, but to let

themselves out the side door. He slipped quietly away to the sounds of a young

girl entering the water in a yellow polka-dot bikini: the children not really listening

to his soft footfalls climbing the stairs. They were too busy shrieking to

every twang and hit of the soccer ball.

0 comments:

Post a Comment